Nel pannello che introduce la mostra “Voci di Pietra – dalle collezioni epigrafiche del Castello Ursino di Catania- curata dal Professor in Ancient History dell’Università di Oxforf Jonathan R.W. Prag – in collaborazione con il Progetto di Alternanza scuola-lavoro con il Liceo Artistico M.M. Lazzaro A.S. 2016/2017 - si legge:

In queste tre sale (10 -11- 12) incontrerete voci della Catania antica, custodite nella pietra. Le antiche iscrizioni forniscono una testimonianza unica, di prima mano, della vita e delle azioni di coloro che ci hanno preceduto. Il Museo Civico di Catania conserva una notevole collezione di circa 500 di questi testi, di cui si presenta qui una selezione. In questa sala (n. 10) troverete una introduzione all’epigrafia antica in Sicilia. Nelle due sale seguenti (11 e 12) si presentano esempi di iscrizioni ufficiali pubbliche della Catania romana e di epitaffi funebri degli abitanti di Catania antica (pagana, cristiana ed ebraica).

In these treee rooms, (10-11-12 ndr) you will meet voices of ancient Catania, preserved on stone. Ancient inscriptions provide unique first-hand sources of evidence for the livesand actions of those who came before us. The Civic Museum of Catania preserves a remarkable collection of some 500 of texts, and a selection is presented here.In this room you will find an introduction to ancient epigraphy in Sicily. In the two rooms that follow we present exsemples of official public inscriptions from Roman Catania and of the funerary epitaphs of the citizens of ancient Catania (Pagan, Christian and Hebrew).

CHE COS'E' L'EPIGRAFIA?

Epigrafia è il nome fornito alla pratica di scrivere su materiale durevole, come pietra o metallo (anziché legno, papiro o pergamena). La decisione di incidere un testo è una scelta culturale e non comune ad ogni società. Gli antichi Greci e soprattutto i Romani incisero testi in grandi quantità (ne sopravvivono fino ad un milione); altri, come i Fenici, ne produssero molti di meno. Le iscrizioni più comuni sono gli epitaffi funerari (70%) ma molti altri tipi di documenti venivano incisi, sia pubblici (per esempio leggi, trattati, iscrizioni onorarie) che privati (per esempio maledizioni).

WHAT IS EPIGRAPHY?

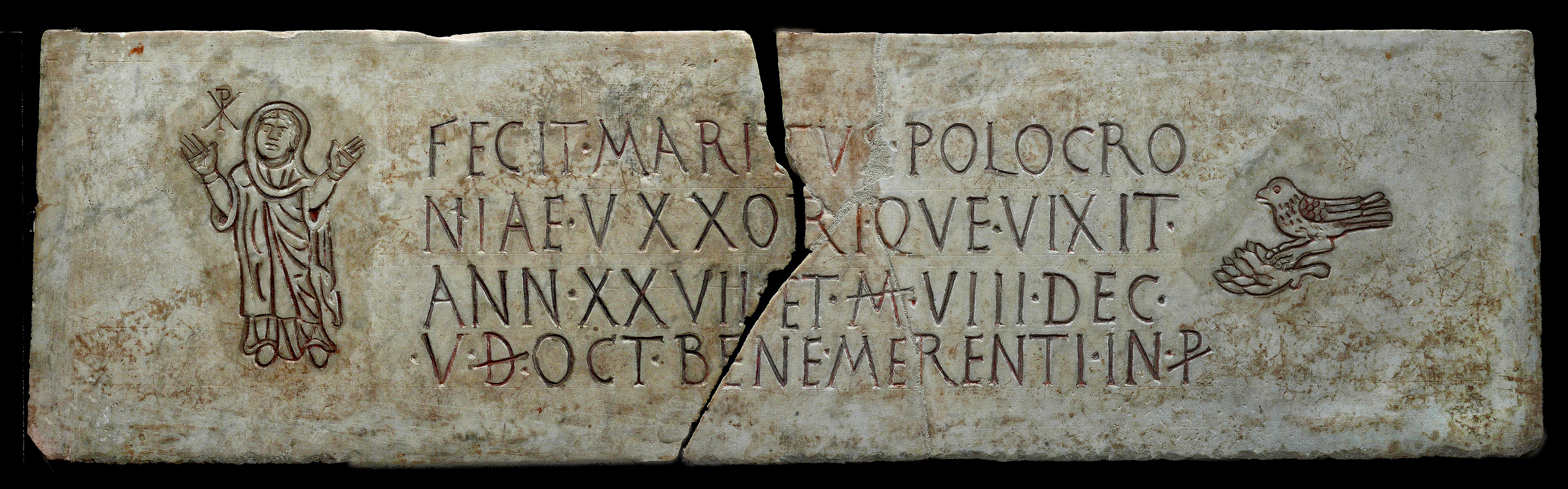

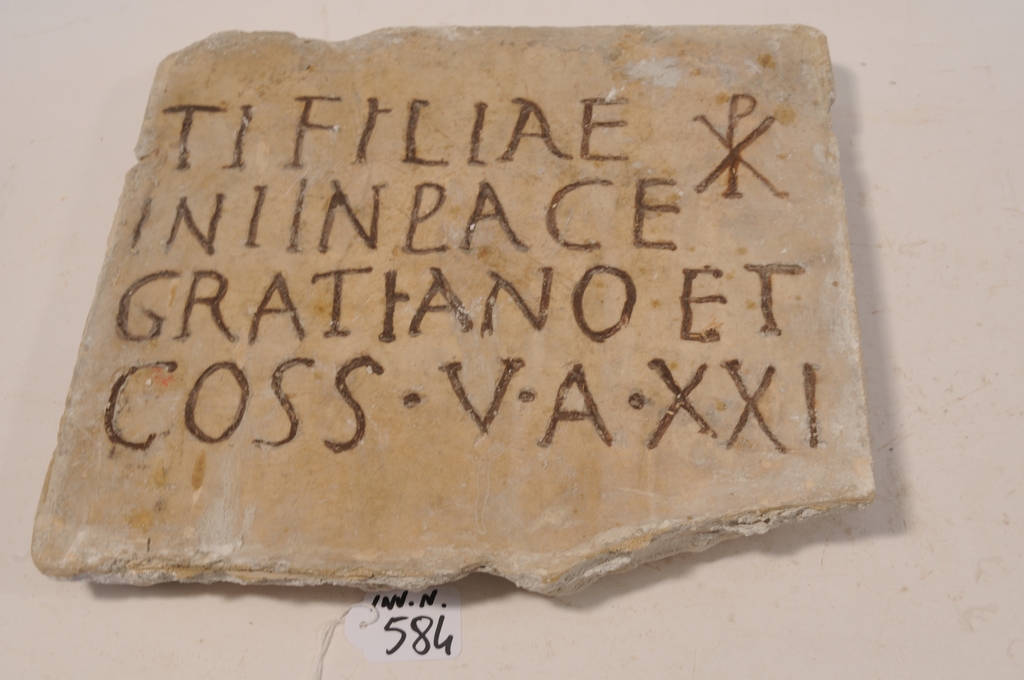

Epigraphy is the name given to the practice of writing texts on durable materials, such as stone or metal ( instead of wood, papyrus or vellum). The decision to engrave a text is a cultural choise, and not common to every society. The ancient Greeks, and above all the Romans, engraved texts in very large numbers ( as many as 1 million survive) ; others, such as the Phoenicians, did so much less. The most common inscriptions are funerary epitaphs (c. 70%), but many other types of document werww also engraved, both public( e.g. laws, treaties, honours) and private (e.g. curses). Inscriptions reflect a deliberate choice to make a text permanent, often for public display - as a result they are not necessarily the same as the original document, and they always reflect a conscious effort to present a text, and must be read accordingly.

Because the material is durable, inscriptions are valuable source of evidence for many aspects of ancient society; languages, people, historical events, public institutions, family structures, personal beliefs, naming practices and much more. For some ancient languages, such as Phoenician or Sikel, inscriptions are our only evidence.

LA COLLEZIONE EPIGRAFICA DEL CASTELLO URSINO

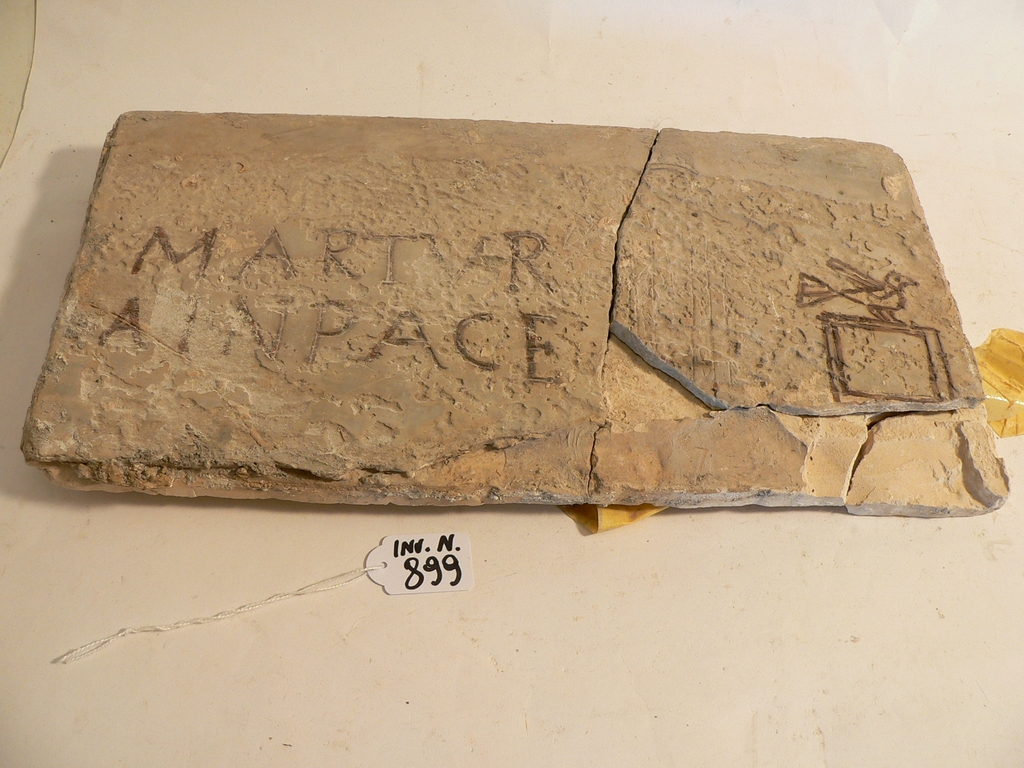

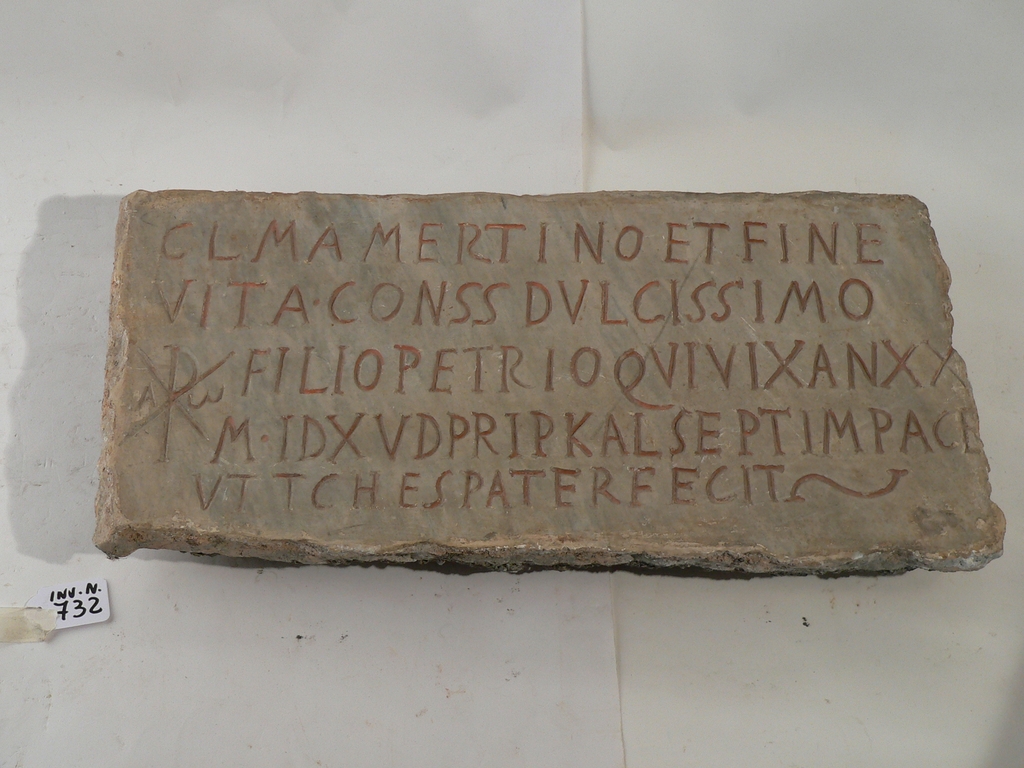

Il fondamento della raccolta epigrafica del Museo Civico è costituito da due collezioni settecentesche catanesi: la collezione dei Benedettini di San Nicolò l’Arena e quella di Ignazio Paternò Castello, principe di Biscari; ne fanno parte inoltre epigrafi provenienti da raccolte minori catanesi e altre rinvenute negli scavi ottocenteschi e novecenteschi. Sia la collezione dei Padri Benedettini sia quella del principe di Biscari sono costituite da materiali archeologici che da iscrizioni per lo più provenienti da contesti siciliani, catanesi in particolare, frutto di recuperi e di scavi, oppure da acquisti effettuati soprattutto nei mercati antiquari di Roma. Tali acquisti devono attribuirsi in gran parte alla mediazione del Priore Benedettino Placido Scammacca, zio del principe di Biscari. Proprio a Scammacca si deve l’arrivo di alcune epigrafi cristiane provenienti dalla catacomba di Domitilla esposte in questa sala insieme ad affreschi provenienti dalla stessa catacomba. Staccati da diversi settori del cimitero romano, questi frammenti di affreschi confluirono nelle collezioni del Principe di Biscari che se ne servì soprattutto per arricchire il suo museo, utilizzando alcune epigrafi che riportano il cognomen Paternus, per glorificare le origini della famiglia Paternò Castello.

The nucleus of the epigraphic collection of the Museum consists of two collections from eighteenth-century Catania: that of the Benedictine monks of S.Nicolò l’Arena, and the collectionof Ignazio Paternò Castello, Prince of Biscari. There are also some inscriptions from smaller local collections and from excavations in the ninetheenth and twentieth centuries.

The collections of the Benedictine monks and the Prince of Biscari contain a variety of archaeological materil and inscriptions. Most of this material comes from Sicily, and especially from Catania, either from chance finds and excavations, or purchases, often from the antiquites market in Rome. Many of these acquisitions were facilitated by the Benedictine prior Placido Scammacca, uncle of the Prince of Biscari.

It is due to Scammacca that the Christian epitaphs and frescoes on display in this room came into the museum, originally from the catacomb of Domitilla in Rome. Removed from different zones of the Roman cemetery, these frescoes were united in the collection of the Prince of Biscari in order to enrich his private museum. In a similar fashion, he brought together several inscriptions which include the Roman cognomen Paternus, to glorify the origins of his family, Paternò Castello.

LE CATACOMBE DI DOMITILLA

Sono tra i più antichi e vasti cimiteri sotterranei di Roma si estendono lungo l’antica via Ardeatina con 17 km di gallerie su quattro differenti livelli per un totale di 150.000 sepolture e una Basilica sotterranea. Le prime gallerie furono scavate tra il II e il III sec. d.C nella proprietà della patrizia Flavia Domitilla che, secondo la tradizione, mise a disposizione della comunità cristiana i suoi possedimenti sulla Ardeatina, seguendo una pratica allora frequente. In origine erano costituite da nuclei indipendenti, tra i più antichi l’ipogeo dei Flavi e la regione di Ampliato. Fra questi due primi nuclei si sviluppò una grande area che in un primo tempo era indipendente. Una zona del cimitero fu probabilmente riservata ai lavoratori dell’annona, come si evince dalle pitture. In questo cimitero si trovano alcune delle più antiche pitture catacombali.

THE CATACOMBS OF DOMITILLA

These catacombs are among the oldest and largest underground cemeteries in Roma. They extend along a ncient via Ardeatina consisting of 17 km og galleries over four levels with a total of 150.00 burials and an underground basilica. The first galleries were excavated in the second and third centuries AD, within the property of the patrician Flavia Domitilla, who according to tradition, placed her possessions at the disposal of the Christian community living on the Ardeatina, following a common practice of the time. Originaly the catacombs werw made up of indipendent tomb complexes, the oldest of wich included the hypogenum of the Flavii and the section called of Ampliatus. Between these first two focal points, a large burial aerea developed which was initially indipendent. One part of the cemetery was probabily reserved for those who worked for the provision of the city’s grain supply, as is implied by paintings. The cemetery includes some of the oldest catacomb wall-paintings.

Sono tra i più antichi e vasti cimiteri sotterranei di Roma si estendono lungo l’antica via Ardeatina con 17 km di gallerie su quattro differenti livelli per un totale di 150.000 sepolture e una Basilica sotterranea. Le prime gallerie furono scavate tra il II e il III sec. d.C nella proprietà della patrizia Flavia Domitilla che, secondo la tradizione, mise a disposizione della comunità cristiana i suoi possedimenti sulla Ardeatina, seguendo una pratica allora frequente. In origine erano costituite da nuclei indipendenti, tra i più antichi l’ipogeo dei Flavi e la regione di Ampliato. Fra questi due primi nuclei si sviluppò una grande area che in un primo tempo era indipendente. Una zona del cimitero fu probabilmente riservata ai lavoratori dell’annona, come si evince dalle pitture. In questo cimitero si trovano alcune delle più antiche pitture catacombali.

L’EPIGRAFIA IN SICILIA

I più antichi esempi di epigrafi fenicie e greche si trovano nel Mediterraneo occidentale tra il IX e l’VIII secolo a.C., ad esempio la Stele di Nora, un testo fenicio in Sardegna, forse del IX secolo a.C e la cosiddetta ‘Tazza di Nestore’ da Ischia, un testo greco inciso su un vaso del tardo VIII secolo a.C.

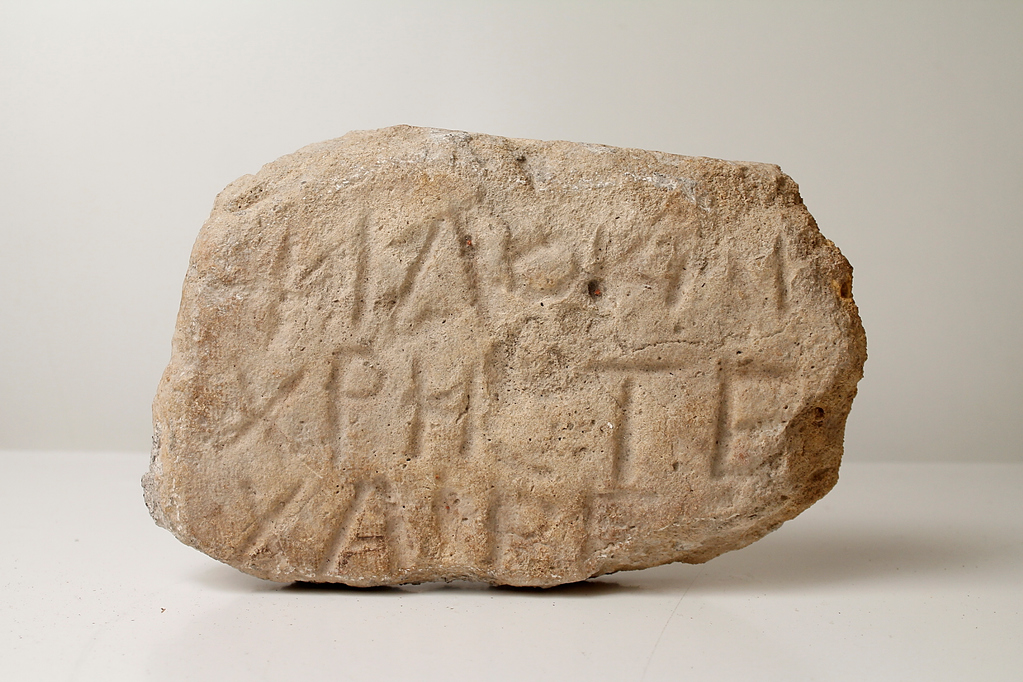

Le prime iscrizioni greche si trovano in Sicilia dal 600 a.C circa un secolo dopo l’arrivo dei primi coloni greci nell’isola e forniscono una importante testimonianza del greco antico. Iscrizioni fenicie si trovano sull’isola (per lo più a Mozia) circa dal V secolo in poi. Sono rare le iscrizioni in lingua sicula e si trovano nella parte orientale dell’isola dal VI al V secolo a.C., ispirate dalla comparsa di epigrafi greche.

Le prime iscrizioni latine appaiono nel III secolo a.C., contemporaneamente alla conquista romana durante le guerre puniche un piccolo numero di iscrizioni osche si trovano a Messina durante lo stesso periodo, grazie ai mercenari campani che occuparono la città. Le epigrafi greche divennero via via più comuni sull’isola a partire dal III secolo a. C., mentre le epigrafi latine, come nel più vasto impero romano, diventarono frequenti a partire dal I secolo a.C. in poi e durante il Principato. Durante i primi quattro secoli dell’impero romano, l’epigrafia latina divenne la più comune sull’isola, anche se l’uso del greco è rimasto diffuso e ci sono esempi occasionali di utilizzo di ebraico. Il volume delle iscrizioni inizia a diminuire dal quarto secolo, e l’epigrafia greca diventa ancora più comune di quanto sia quella latina durante il periodo bizantino. (V-VII secolo d.C.)

EPIGRAPHY IN SICILY

Rare examples of Phoenician and Greek epigraphy are found in the western Mediterranean from the ninth and eighth centuries BC (e.g. Nora stele, a Phoenician text on Sardinia, perhaps ninth century BC; the so-called ‘Nestor’s cup’ from Ischia, a Greek text engraved on a Greek vase in the later eighth century BC). Greek inscriptions are first found on Sicily c.600 BC, around a century after the first Greek settlers arrived on the island, and provide important evidence for early Greek (see fig.no.3) Phoenician inscriptions are found on the island (mostly at Mozia) from perhaps the fifth century onwards(see fig.no.2) Sikel inscriptions are rare, but are found in the east of the island in the sixth and fifth centuries BC, inspired by the appearance of Greek epigraphy( see inscription no.1).

The first Latin inscriptions appear in the third century BC, contemporary with the Roman conquest during the Punic Wars, and a small number of Oscan inscriptions are found at Messina during the same period, erected by the Campanian mercenaries who occupied the city ( see inscription no.2). Greek epigraphy became steadily more common on the island from the third century BC onwards, while Latin epigraphy, in common with the wider Roman empire, became frequent from the first century BC onwards and during the Principate. During the first four centuries of the Roman empire, Latin epigraphy was the most common on the island, although the use of Greek remained widespread,(see inscription no.9), and there are occasional examples of the use of Hebrew( see inscription n.32). The volume of inscriptions begins to decrease by the fourth century, and Greek epigraphy again becomes more common than Latin during the Byzantine period ( fifth- seventh centuries AD).

II sec d.C.

III sec d.C.

IV sec d.C.

366 d.C.

290-325 d.C.

VI-V sec a.C.

II o I secolo a.C.

III sec a.C.

Fine IV sec - Inizio V sec d.C.

I-II sec d.C.

N. inventario:

Soggetto/oggetto:

Autore:

Datazione:

Descrizione:

Materiale e tecnica: