Nel pannello che introduce la mostra “Voci di Pietra – dalle collezioni epigrafiche del Castello Ursino di Catania- curata dal Professor in Ancient History dell’Università di Oxforf Jonathan R.W. Prag – in collaborazione con il Progetto di Alternanza scuola-lavoro con il Liceo Artistico M.M. Lazzaro A.S. 2016/2017 - si legge:

In queste tre sale (10 -11- 12) incontrerete voci della Catania antica, custodite nella pietra. Le antiche iscrizioni forniscono una testimonianza unica, di prima mano, della vita e delle azioni di coloro che ci hanno preceduto. Il Museo Civico di Catania conserva una notevole collezione di circa 500 di questi testi, di cui si presenta qui una selezione. In questa sala (n. 10) troverete una introduzione all’epigrafia antica in Sicilia. Nelle due sale seguenti (11 e 12) si presentano esempi di iscrizioni ufficiali pubbliche della Catania romana e di epitaffi funebri degli abitanti di Catania antica (pagana, cristiana ed ebraica).

In these treee rooms, (10-11-12 ndr) you will meet voices of ancient Catania, preserved on stone. Ancient inscriptions provide unique first-hand sources of evidence for the livesand actions of those who came before us. The Civic Museum of Catania preserves a remarkable collection of some 500 of texts, and a selection is presented here.In this room you will find an introduction to ancient epigraphy in Sicily. In the two rooms that follow we present exsemples of official public inscriptions from Roman Catania and of the funerary epitaphs of the citizens of ancient Catania (Pagan, Christian and Hebrew).

CHE COS'E' L'EPIGRAFIA?

Epigrafia è il nome fornito alla pratica di scrivere su materiale durevole, come pietra o metallo (anziché legno, papiro o pergamena). La decisione di incidere un testo è una scelta culturale e non comune ad ogni società. Gli antichi Greci e soprattutto i Romani incisero testi in grandi quantità (ne sopravvivono fino ad un milione); altri, come i Fenici, ne produssero molti di meno. Le iscrizioni più comuni sono gli epitaffi funerari (70%) ma molti altri tipi di documenti venivano incisi, sia pubblici (per esempio leggi, trattati, iscrizioni onorarie) che privati (per esempio maledizioni).

WHAT IS EPIGRAPHY?

Epigraphy is the name given to the practice of writing texts on durable materials, such as stone or metal ( instead of wood, papyrus or vellum). The decision to engrave a text is a cultural choise, and not common to every society. The ancient Greeks, and above all the Romans, engraved texts in very large numbers ( as many as 1 million survive) ; others, such as the Phoenicians, did so much less. The most common inscriptions are funerary epitaphs (c. 70%), but many other types of document werww also engraved, both public( e.g. laws, treaties, honours) and private (e.g. curses). Inscriptions reflect a deliberate choice to make a text permanent, often for public display - as a result they are not necessarily the same as the original document, and they always reflect a conscious effort to present a text, and must be read accordingly.

Because the material is durable, inscriptions are valuable source of evidence for many aspects of ancient society; languages, people, historical events, public institutions, family structures, personal beliefs, naming practices and much more. For some ancient languages, such as Phoenician or Sikel, inscriptions are our only evidence.

ISCRIZIONI EBRAICHE NELLA CATANIA ANTICA

Le testimonianze relative agli ebrei in Sicilia iniziano quasi interamente dal IV sec. d.C. in poi (l'iscrizione 32, del 383 d.C., è il più antico testo databile). È molto probabile, tuttavia, che la comunità fosse già ben radicata prima di quella data. I documenti sono per Io più testi funerari, amuleti e altri oggetti iscritti, spesso con simboli ebraici, come la menorah.

In Sicilia, come per i primi cristiani, anche per gli ebrei la documentazione proviene dalla zona sud orientale dell'isola e diviene evidente in concomitanza con l'accettazione del cristianesimo da parte dello Stato nel corso del IV secolo.

Le iscrizioni funerarie suggeriscono che cristiani ed ebrei coesistessero: avevano sepolture contigue e il linguaggio usato nei testi spesso si sovrappone, come per esempio nella frase “nel grembo di Abramo” neII'iscrizione 34. Catania è una delle più ricche fonti di testi ebraici della Sicilia e i riferimenti alle leggi ebraiche e agli anziani (presbyteroi) fanno pensare all'esistenza di una sinagoga.

Tutti i testi ebraici rinvenuti in Sicilia sono in greco: le uniche eccezioni sono una lamina d'oro da Comiso in ebraico e l'iscrizione di Aurelius Samohil (iscrizione 32), che è il più Iungo testo latino antico della diaspora ebraica in occidente. Qui l'ebraico è stereotipato, cosa che indica piuttosto un ossequio alla tradizione che non una piena conoscenza della Iingua. Il latino è contrassegnato da errori formali (ad es. mi——mihi e oxsoris——uxori) ed è probabile che fosse scelto non per familiarità, ma perché si trattava della Iingua ufficiale dei documenti pubblici, come già visto nella sala precedente. Aurelius è un nome romano comune; Samuel è altrettanto comune in ambiente ebraico. L'iscrizione mira dunque a presentare Aurelius come un membro della élite locale. É da notare come Aurelius per avere protezione si appelli in ugual modo all'autorità romana, giudaica e divina (le minacce contro chi danneggia una tomba sono usuali neII'antichità).

Pace su lsraele. Amen, amen pace. Samuel.

Io, Aurelius Samohil (——Samuel), acquistai una tomba per me e mia moglie Lassia Irene, che completò il suo percorso assegnato dal Fato dodici giorni prima delle calende di novembre (——21 ottobre), giorno di Venere (——venerdì), nell'ottava luna (nel mese ebraico di Heshwan), consoli Merobaudes per la seconda volta e Saturnino (——383 d.C.); visse ventitre anni con pace. Vi scongiuro per le vittorie di coloro che governano, parimenti vi scongiuro per gli onori dei patriarchi, parimenti vi scongiuro per la Iegge che il signore ha dato agli ebrei: nessuno apra la tomba e metta il corpo di qualcun altro sopra le nostre ossa; ma se qualcuno dovesse aprirlo, possa egli dare al fisco il peso di dieci libbre di argento.

JEWISH INSCRIPTIONS IN ANCIENT CArA/V/A

The evidence for Jews in Sicily dates almost entirely to the fourth century AD and later (inscription no.32 is the earliest datable text, 383 AD). It is, however, very likely that the community was established well before that date. The evidence is mostly funerary texts, amulets and other inscribed objects, often with Jewish symbols, such as the menorah.

Like the early Christians in Sicily, the evidence for Judaism comes from the south-east of the island, and it becomes visit/e alongside the state acceptance of Christianity in the fourth century. The funerary inscriptions auggesf that Jewa and christians co-exhaled: they were alien buried c/ose together, and the language of the fexfs often overlaps, as for example in the phrase ’in the lap ofAbraham’in inscription no.34. Catania is one of the richest sources of Jewish texts from Sicily, and the references to Jewish law and to elders (presbyteroi} suggest the presence of a synagogue.

All of the Jewish fexfs from Sicily are in Greek: the only exceptions are a gold sheet from Comiso in Hebrew and the inscription of Aurelius Samohil (inscription no.32), which is the longest ancient Latin text from the Jewish diaspora in the west. The Hebrew is formulaic and soggesfs a respect for tradition rather than full knowledge of the language. The Latin shows formal errors (e.g. mi——mihi, oxsoris=uxori , and it is likely that Latin was chosen not because it was familiar but because it was the high status language of public documents, as is visible in the previous room. Aurelius is a common Roman name; Samuel a common Jewish one. The inscription aims fa present Aurelius as a member of the local élite. It is notable that Aurelius appeals equally to Roman, Jewish and divine authority for protection (threats against those who desecrate a tomb are common in antiquity).

Peace upon Israel. Amen, amen, peace. Samuel.

I, Aurelius Samohil (=SamueI), bought the memorial for myself and my wife Lassia Irene, who completed her allotted span on the twelfth day before the Kalends of November (=21 October), the day of Venus (=Friday), in the eighth moon (Jewish month of Heshwan), when Merobaudes for the second time and Saturninus were consuls (=383 AD); she lived for twenty-three years with peace. I adjure you by the victories (of those) who rule, likewise I adjure you by the honours of the patriarchs, likewise I adjure you by the law which the lord gave the Jews: let no-one open the memorial and put the body of someone else on top of our bones; but if anyone does open it, let them give ten pounds of silver to the treasury.

ISCRIZIONI FUNERARIE DI ETA’IMPERIALE

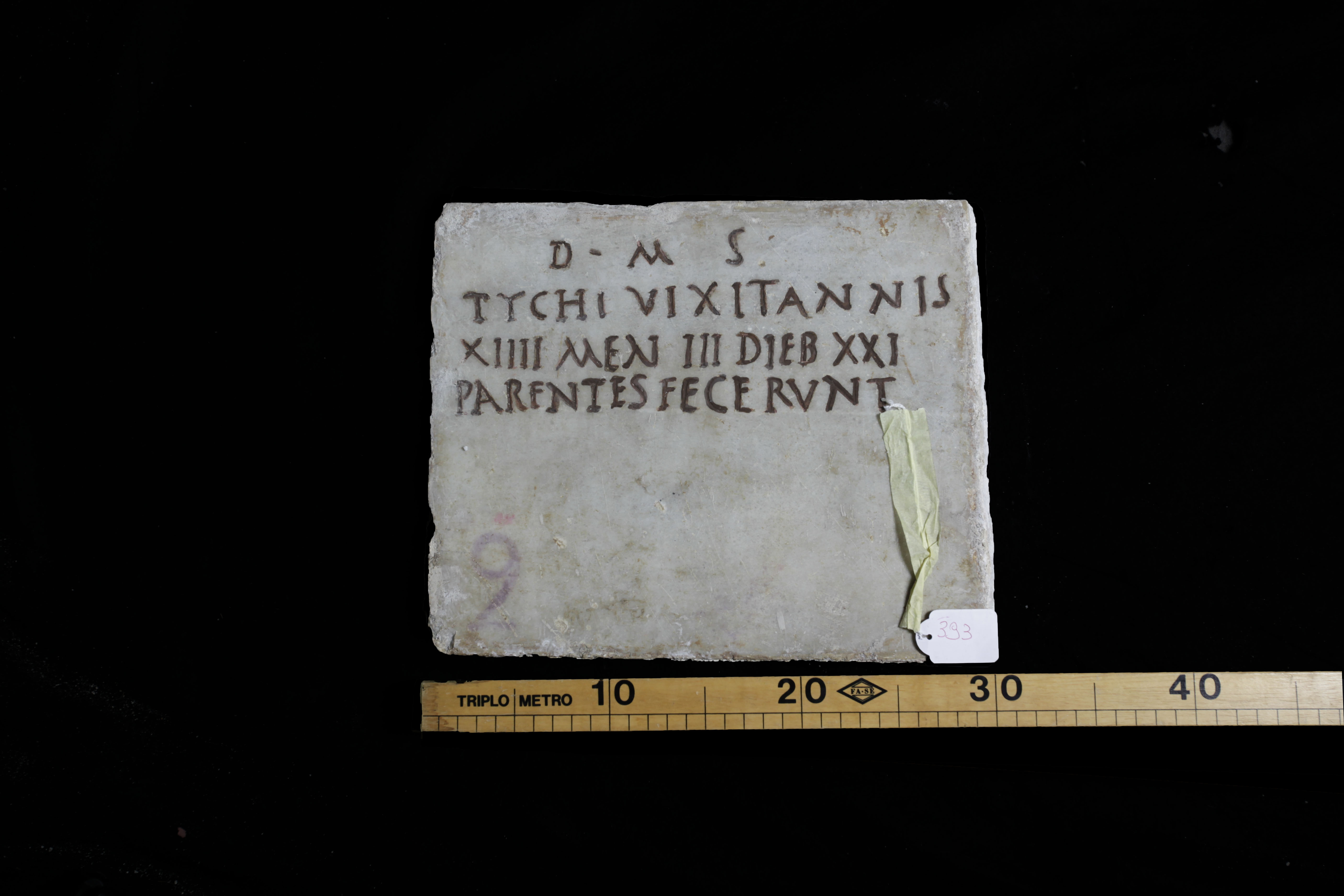

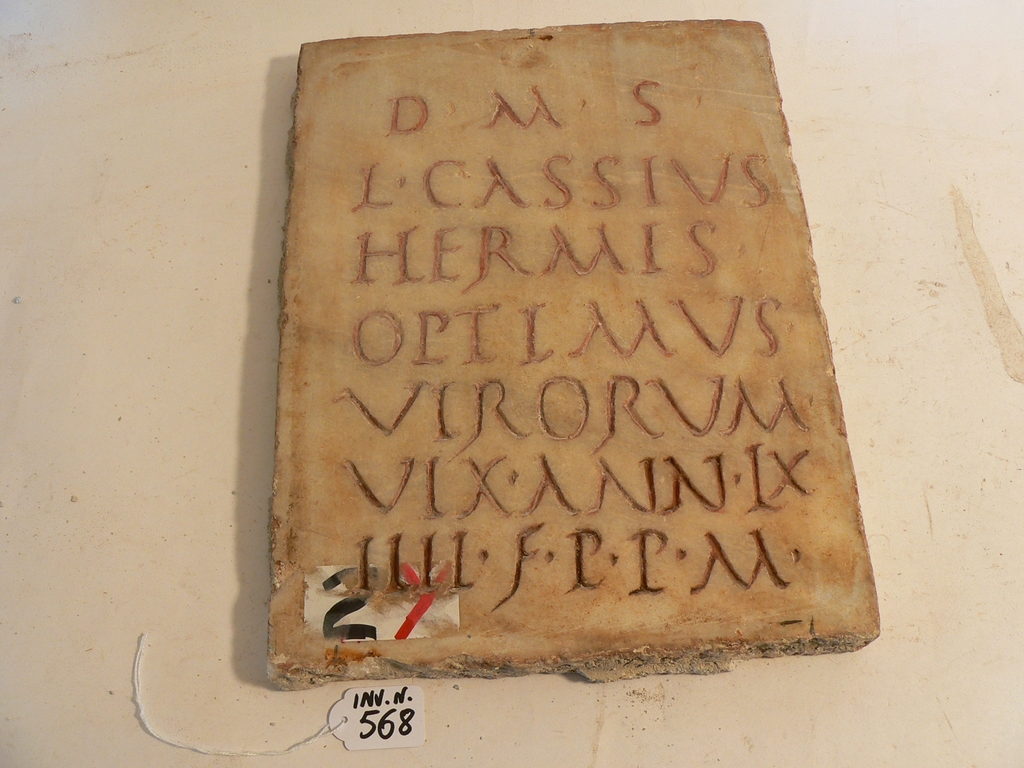

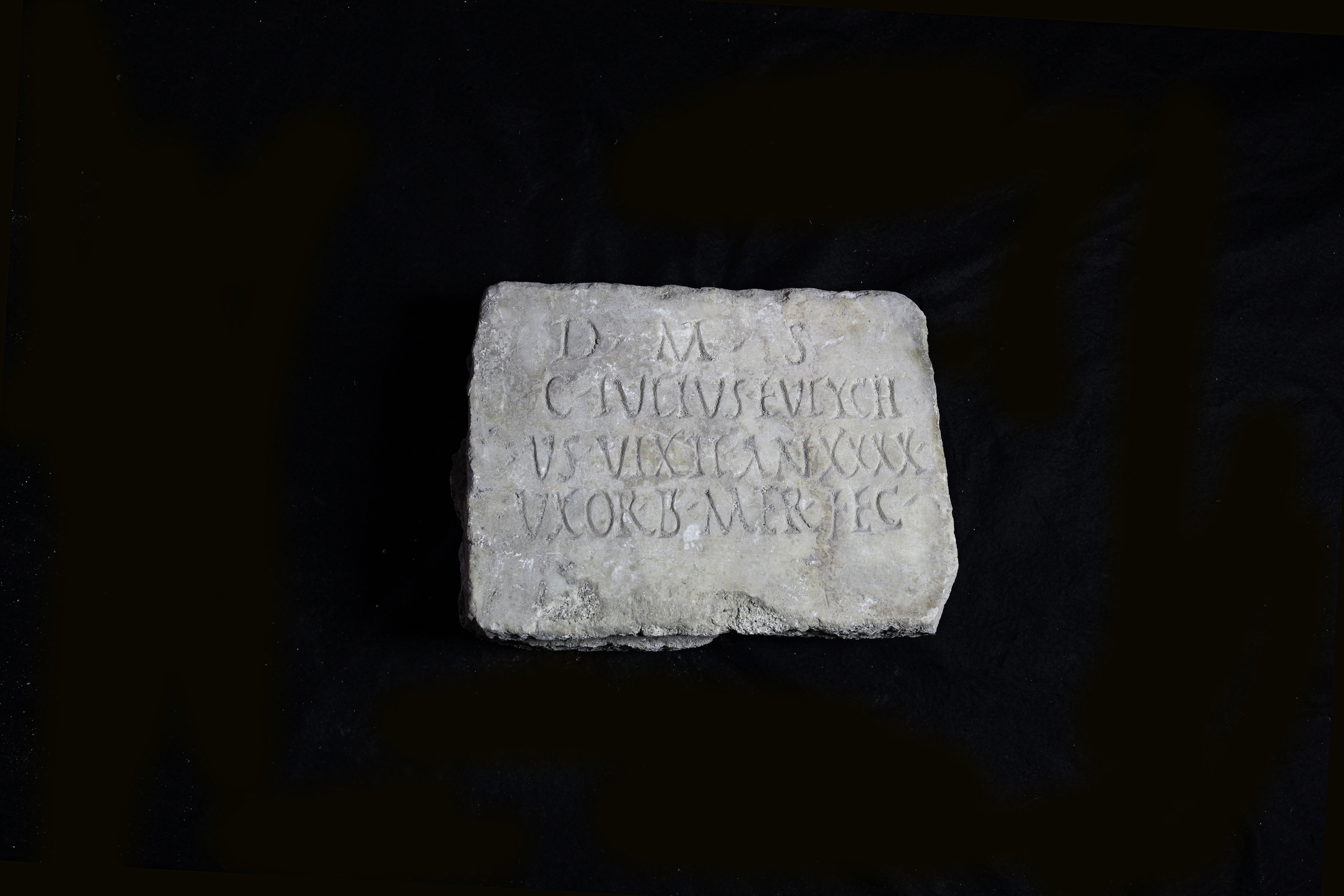

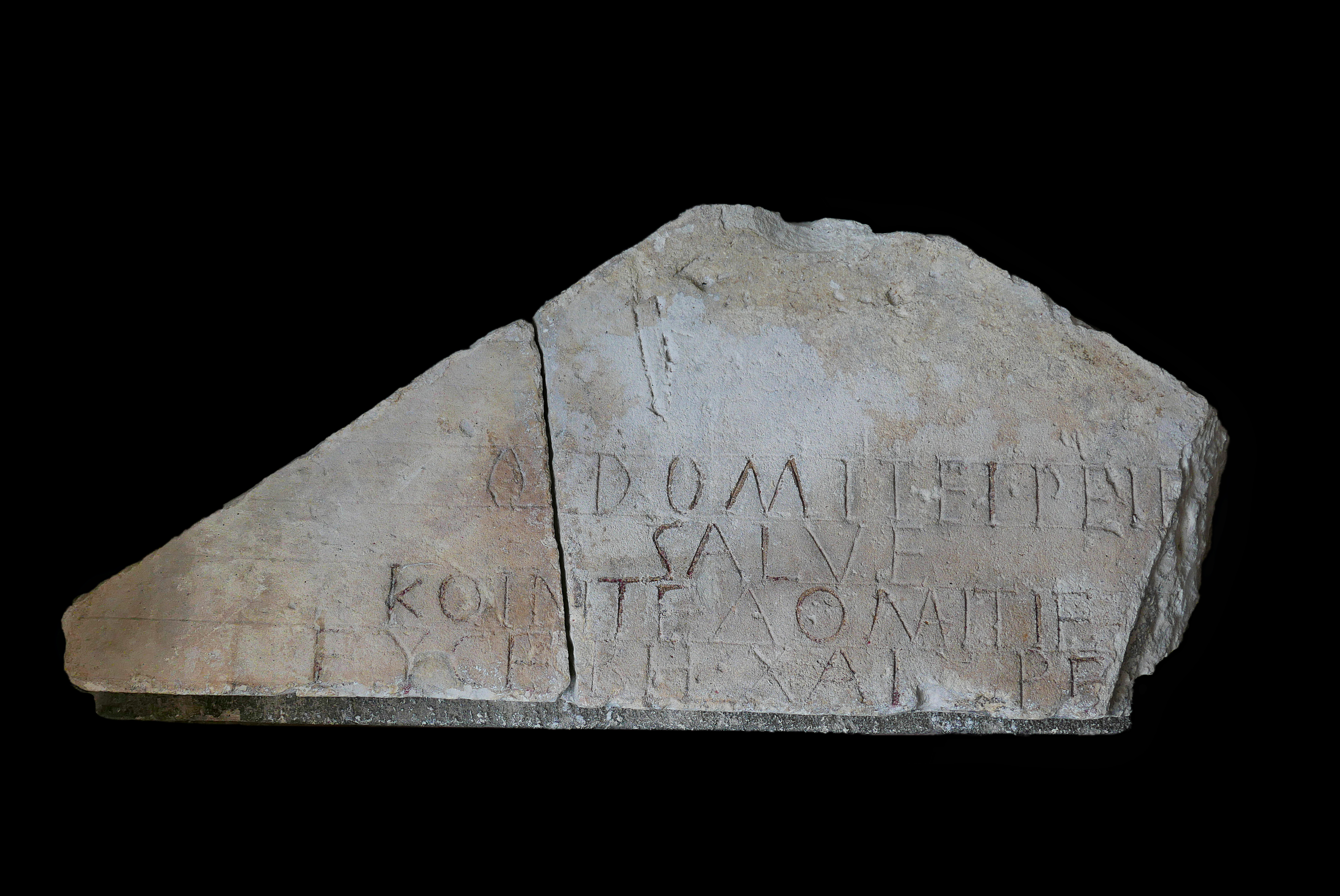

Le iscrizioni funerarie costituiscono il 70% di tutta l’epigrafia greca e romana. Molte riportano poco più che il semplice nome del defunto. Tuttavia in epoca romana era comune l’aggiunta di altri dettagli, come l’età, informazioni sulla vita, parole di lutto o di lode e il nome di chi dedicava la lapide. I testi sono caratterizzati da un formulario e appaiono ripetitivi, ma la particolare scelta di inserire alcune informazioni consente di far trapelare il dolore personale (per esempio l’età esatta di Tyche in iscrizione 20). Le iscrizioni individuano il luogo della sepoltura. Durante la prima età imperiale era comune la cremazione, ma l’inumazione divenne la norma dal III sec. d.C. Le lastre iscritte erano fissate alle pareti delle tombe. Camere funerarie più grandi, dette columbaria, con molteplici nicchie per sepolture furono costruite per famiglie e confraternite (collegia). Le ceneri erano collocate nelle nicchie con sotto le iscrizioni, come si vede nella ricostruzione, ma erano usate anche delle urne iscritte. Per le inumazioni venivano usate nicchie più grandi, tombe scavate nel terreno, o sarcofagi in pietra (esempi nel cortile del Castello). L’epigrafia funeraria documenta i nomi, le strutture familiari, la religione e la lingua: così noi conosciamo questi antichi abitanti di Catania solo grazie alle loro lapidi funerarie. Catania era una città greca che divenne colonia romana e una buona parte dei testi mostra come lingua e cultura si intreccino in un ambiente multilingue: a esempio la formula latina Dis Manibus viene tradotta (iscrizione 25) e abbreviata a imitazione dello stile romano (iscrizione 26 e 27); i testi greci possono far uso dei numerali romani (iscrizione 26); nomi latini sono trascritti in greco (iscrizioni 22, 23 e 24). Questo tipo di “interferenza” fornisce indizi sullo sviluppo delle lingue e sulle scelte all’interno di esse. Sebbene a Catania molte persone continuassero a parlare greco, il latino era comunque la lingua pubblica usata ai più alti livelli e questo ha influenzato la scelta della lingua dei testi epigrafici.

FUNERARY INSCRIPTIONS OF THE IMPERIAL PERIOD

Funerary inscriptions make up about 70% of all Greek and Roman epigraphy. Many are little more than the name of the deceased (see inscription n.3). In the Roman periodi t was common to add other detals, such an age at death, biographical information, words of mourning or praise, and information on who set up the tombstone. The texts are very, formularic and ripetitive, but the specific choice of elements can still reveal the personl grief (e.g. detailed age of Tyche in inscription no. 20).

Inscription marked the place of burial, in the early empire cremation was common, but inhumation was normalfrom the third century AD. Inscribed plaques werw fixed t the walls of tombs. Larger, tombs, called columbaris, werw built for households and burial clube (collegia), with multiple niches for burials (fig. no. 1)The ashes were placed in the niches with inscriptions below, as in the reconstruction, inscribed chests were also used (inscriptions nos. 4 and 17). For inhumation lager niches, tombs cut into the ground, or stone sarcofagy were used (examples in the courtyard, figs. nos. 2 and 3).

Funerary epigraphy provides evidence for names, family structures, religion and language. We only know these citizens of Catania because of their tombstones. Catania was Greek city that became a Roman colony and many of the taxts show how launguage and culture cross over in a multi- lingual environment: the Latin formula Dis Manibus is translanted ( inscription no.25) and abbreviated in imitation of Roman style ( inscription nos. 26 and 27); Greek texts can use Roman numerals( inscription no. 26); Latin names are transcribed in Greek (inscriptions nos. 22, 23, and 24). This sort of ‘interference’ provides clues about the development of languages, and choices between them. In Catania many people will still have spoken Greek, but Latin was the higher status public language and this affected their choices.

IL CRISTIANESIMO IN SICILIA

Sebbene S. Paolo abbia fatto tappa a Siracusa durante il suo viaggio verso Roma le più antiche testimonianze dell’ordinamento in Sicilia, per lo più sepolture, risalgono al III sec.d.C. Sotto l’impero romano i cristiani furono inizialmente perseguitati, ma nel 313 d.C, con l’imperatore Costantino, la loro fede fu riconosciuta, per diventare religione di stato sotto Teodosio (379 – 395 d.C.). Le testimonianze subiscono poi un veloce incremento nel corso del IV secolo. Le più antiche comunità cristiane di Sicilia si trovano nelle città della zona orientale come Catania, Siracusa. Sono rari gli epitaffi del III secolo, ma l’iscrizione 29 potrebbe essere il più antico proveniente da Catania; mentre l’iscrizione 28 è uno dei più antichi epitaffi cristiani datati della Sicilia (345 d.C.).

Le più antiche iscrizioni funerarie cristiane non sempre possono essere distinte da quelle pagane, poiché spesso le sepolture avvenivano nei medesimi siti e il frasario usato era molto simile. Tuttavia le differenze nelle credenze e la costituzione di una comunità basata sulla fede (e la sepoltura all’interno di quelle comunità, in particolare nelle catacombe) comportò lo sviluppo nelle iscrizioni funerarie cristiane di caratteristiche e linguaggio peculiari. Ad esempio, la credenza cristiana nell’aldilà significò che la data della morte (entrata nell’aldilà) fosse importante e che venisse registrata, diversamente da quanto avveniva negli epitaffi pagani. Ai testi vennero inoltre comunemente aggiunti simboli cristiani, come il chi-rho, pesci, colombe e rami di palma (fig.1).

Catania fu la patria della prima martire siciliana S. Agata, morta nel 251 d.C. Due iscrizioni del IV secolo provenienti da Catania fanno riferimento alla Santa: l’epigrafe di Iulia Florentina (fig.2), la bambina morta ad Hybla (=Paternò, da cui proviene l’iscrizione 16) all’età di diciotto mesi, che fu seppellita di fronte alle porte della tomba dei martiri cristiani a Catania ( probabilmente la tomba di Agata e forse di Euplio) e l’epitaffio del piccolo Agathon (iscrizione 31) che si conclude con una preghiera a S.Agata:

“Tutta la terra e il vasto etere generano per te, o Morte. All’improvviso mi hai strappato via il bambino, che necessità c’era? Infatti se fosse invecchiato, non sarebbe stato pur sempre tuo? Il signore Agathon nacque quindici giorni prima delle calende di novembre (=18 ottobre) nel giorno di Kronos. Visse undici mesi; morì dieci giorni prima delle calende di novembre (=23 agosto) nel giorno del Sole. Signora Agatha (conceda) la pace di Agathon”.

Traduzione del testo di Iulia Florentina:

A Iulia Florentina, infante dolcissima e innocentissima, divenuta fedele, il padre pose (questo monumento); lei, il giorno prima delle none di marzo (= 6 marzo) prima del far del giorno, nata pagana, nell’anno in cui Zoilos era correttore (governatore) della provincia, avendo vissuto diciotto mesi e ventidue giorni fu fatta fedele (divenne cristiana), all’ora ottava della notte rendendo l’ultimo sospiro, sopravvisse quattro ore sì da ripetere gli atti consueti. Morì a Ibla la prima ora nel settimo giorno prima delle calende di ottobre (= 25 settembre). Mentre entrambi i genitori in ogni momento della notte lamentavano la sua morte, la voce di Dio emerse per ordinare loro di non piangere sulla ragazza morta. Il suo corpo fu sepolto dal presbitero nella sua tomba cristiana davanti alle porte del santuario dei martiri cristiani il quarto giorno prima delle none di ottobre (=3 ottobre).

CRISTIANITY IN SICILY

Although St. Paul stopped briefly in Syracuse in his way to Rome the earliest evidence for Christianity in Sicily comes from the third century AD, mostly in the form of burials. Christians were initially persecuted under Rome, but the faith was accepted under the Emperor Costantine (in AD 313) and fully established under the Emperor Theodosius (AD 379-395) . The evidence increases rapidly during the fourth century. The early Christian communities in Sicily are mostly found in the eastern cities such as Catania and Syracuse. Third-century epithaphs are rare ( Inscription no.29 may be the earliest from Catania). Inscription no.28 is one of the earliest dated Christian epigraphs from Sicily, from AD 345.

Early Christian epitaphs cannot always be distinguished from pagan ones, because Christians and pagans were often buried in the same places and used very similar language. However, the difference in beliefs and the creation of a community based on faith (and burial within that community, especially in catacombs) mean that Christian funerary inscriptions soon developed distinctive features and language. For example, the Christian belief in the afterlife means that the date of death ( entryinto the afterlife) is important and is recorder, unlike in pagan epitaphs. Christian symbols are slso commonly added to the texts, such as the chi-rho, fish, doves, and palm branches (see fig.no.1).

Catania was the home to the first Sicilian martyr, St. Agatha (died 251 AD). Two fourth-century inscriptions from Catania refer to the saint: the epitaph of the infant Iulia Florentina (fig.no.2), who died a Hybla (=Paternò, see inscription no.16) aged eighteen month, and was buried in front of the doors of the Shrine of the Christian Martyrs in Catania ( this must be a shrine Agatha and perhaps Euplus) :

To Iulia Florentina, a most sweet and innocent child, who became an adherent of the faith, (this monument) her father has set up. She was born a pagan before dawn on the day before the Nones of March ( =6 March) in the year that Zolius was corrector (governor) of the province, and having lived eighteen months and twenty-two days she was made faithful (i.e. became a Christian) at the eighth hour of the night, when breathing her last, and survivied four hours restored to her former self. She died at Hybla at the first hour on the seventh day before the Kalends of October (= 25 September). While both parents at every moment throughout the night were lamenting her death, the voice of majesty issued forth to order them not to weep over the dead girl. Her body was buried by the presbyter in her Christian grave in front of the doors of the Shrine of the Christian Martyrs on the fourth day before the Nones of October (=3 October).

and the epitaph of the infant Agathon (inscription no.31), which ends with a prayer to S. Agatha:

“All the earth and the air in its wide expanses begets you, o Death. On a sudden, you snatched away my babe – or was there some necessity, for if he had grown old, would he not still have been yours? Master Agathon was born the fifteenth day before the Kalends of November (= 18 October), on the day of Kronos; he lived eleven months; he died the tenth day before the Kalends of September (=23rd August), on the day of the Sun. Lady Agatha, (grant) peace for Agathon!”.

II-III sec d.C.

I-II sec d.C.

I-II sec d.C.

V sec d.C.

V sec d.C.

I-II sec d.C.

I sec a.C. / I sec d.C.

V sec d.C.

N. inventario:

Soggetto/oggetto:

Autore:

Datazione:

Descrizione:

Materiale e tecnica: